CISO Elevation in 2026: Why Cybersecurity Leadership Is Moving to the C-Suite and Board Tables

Table of Content

- Cybersecurity leadership is moving to enterprise decision-making. Boards now treat CISOs as business control executives with authority to pause launches, block vendors, and govern risk exceptions.

- Digital revenue and operational resilience drive CISO elevation. Cyber risk directly impacts subscription revenue, contract renewals, and business continuity, making security a P&L issue.

- AI security governance is becoming a CFO and GC priority. Shadow AI and impersonation threats are creating tangible financial loss, requiring CISOs to partner on fraud prevention and customer protection.

- Organizations are splitting the CISO role for scale. Forward-thinking companies are separating strategic governance (CISO) from technical delivery (VP Security Engineering) to manage complexity.

The conversation regarding cyber risk has fundamentally changed within the boardroom. It no longer resembles a technical update on firewalls or patching schedules. Instead, directors now discuss cybersecurity with the same gravity and financial scrutiny applied to liquidity ratios, supplier concentration, and operational downtime. This shift is not merely theoretical.

Data from Deloitte’s 2025 Future of Cyber Survey indicated that 41% of boards were already addressing cyber issues on a monthly basis, a cadence reserved for critical enterprise risks rather than functional IT updates.

The pivotal change shaping 2026 is the reclassification of security leadership. Security is increasingly being treated as a business control function rather than an IT subdomain. This shift elevates the CISO from an advisory role to an executive one, granting specific decision rights that influence product roadmaps and capital allocation.

As we move ahead, this blog examines the market forces likely to drive CISO elevation, the practical impact of a “seat at the table” on decision making, and why this shift is expected to create high-stakes hiring demand for a new caliber of security leader.

What’s driving CISO Elevation

While SEC disclosure rules forced a baseline of transparency, the real pressure on boards right now is not coming from regulators. It is coming from the P&L. The shift from “compliance officer” to “executive officer” is being driven by three specific market forces that have made cyber risk a direct variable in revenue performance and capital allocation.

Digital Revenue Makes Cyber an Operating-number Problem

For modern enterprises, cybersecurity is no longer just about protecting data; it is about protecting the revenue engine itself. With reliance on subscription models, API-based partner channels, and real-time digital conversion, the cost of disruption is now measured in missed quarterly targets. Boards are feeling this impact directly through increased customer churn, stalled contract renewals, and penalty-laden SLA breaches following service disruptions.

In 2025, we saw this reality crystallize when major retailers faced ransomware attacks that did not just steal data but halted online orders for weeks, directly slashing profits by hundreds of millions. This pulls the CISO into the center of executive strategy because security tradeoffs now manifest as product delays, margin erosion, and lost market share.

As McKinsey noted in its 2025 analysis, digital trust has graduated from an IT concern to a competitive differentiator that determines whether customers stay or leave.

Business Interruption is now the Board’s Common Denominator

Most organizations have learned to absorb a contained data breach, but few can survive days of operational paralysis across revenue-generating systems. Currently, operational resilience has become a shared agenda for the COO, CIO, and CISO, with the CEO increasingly acting as the arbitrator of risk tradeoffs.

The CISO’s credibility in the boardroom now hinges on their ability to articulate “minimum viability”, defining exactly which assets, processes, and personnel are required to keep the business running during a crisis.

This shift focuses on recovery capability rather than just prevention. Deloitte’s 2025 resilience frameworks emphasize that keeping pace with threats is a top strategic challenge, requiring CISOs to lead “cleanroom recovery” strategies that ensure a rapid return to business-as-usual rather than prolonged chaos. When a CISO can speak plainly about outage costs and service dependencies, they move from a technical advisor to an operational leader.

AI adoption Raises New Abuse Paths that Hit Finance and Brand

The rapid integration of AI into customer workflows and employee decision-making has opened volatile new risk vectors. Boards are now scrutinizing “shadow AI,” or unsanctioned tools used by employees, which Gartner predicts would drive 40% of AI-related breaches by 2030.

Beyond internal leaks, the rise of AI-enabled impersonation and automated fraud is pulling the CISO into tighter alignment with the CFO and General Counsel to combat direct financial loss.

The damage is tangible. IBM’s 2025 research found that breaches involving unsanctioned AI cost significantly more and took longer to detect than traditional incidents. With 41% of security leaders citing AI-driven insider threats as a primary concern, companies are forced to upgrade the scope of their security leadership.

The “AI security talent gap” is real, pushing boards to find leaders who can govern these automated decision flows without stifling innovation.

Talk to Vantedge Search about board-level CISO hiring

What Changes When Security Leadership Moves from IT to Enterprise Leadership

The difference between a functional head and an enterprise leader is defined by decision rights. When security leadership reports purely through IT, its power is often limited to recommendation and influence. When it elevates to enterprise leadership, that influence hardens into the authority to stop, start, or shape business initiatives based on risk appetite.

Decision Rights are the Real Difference Between “Adviser” and “Executive”

The most practical question boards can ask in 2026 is not “Do we have a CISO?” but “What is our CISO authorized to decide?” In mature organizations, the CISO has transitioned from a consultative voice to a decision-maker with specific veto and approval powers.

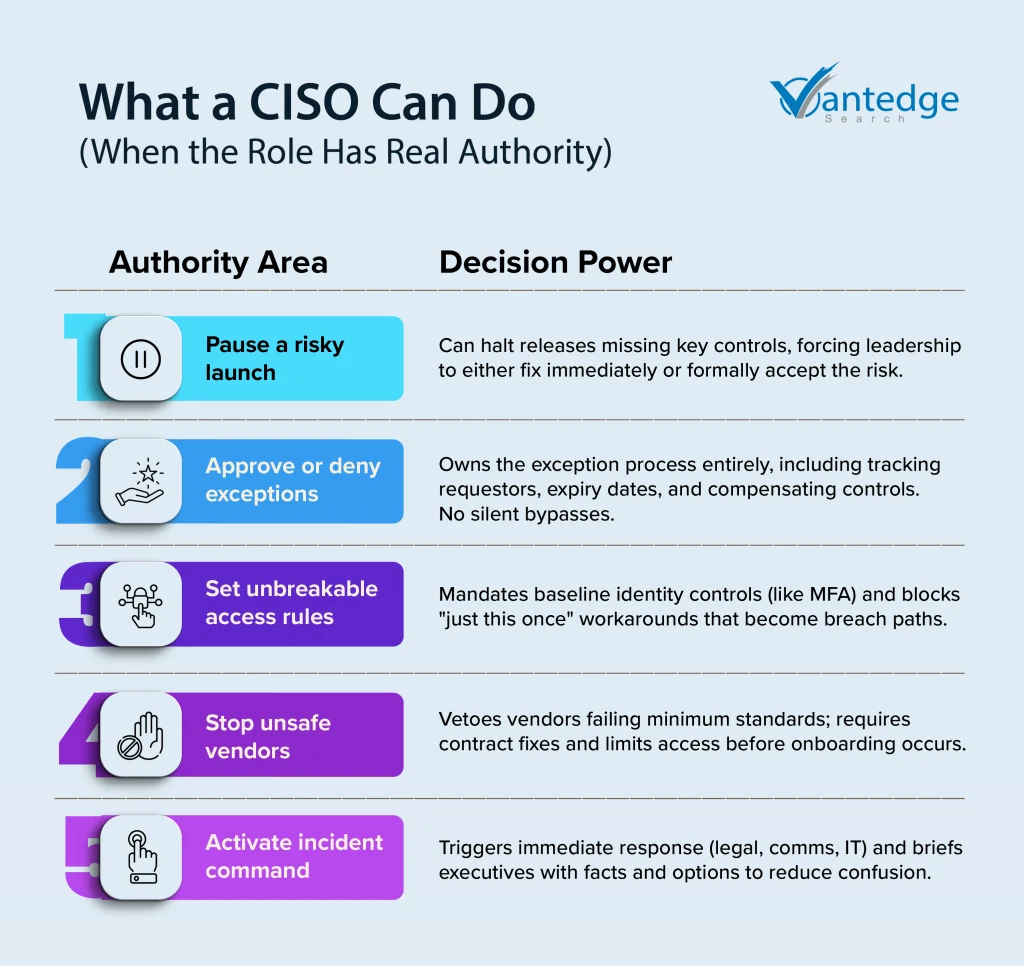

To be effective, the modern CISO role must include specific operational authorities:

- Pause a risky launch: A CISO must have the ability to pause a release when key controls are missing. That forces a clear leadership decision to either fix the issue immediately, cut the scope, or ship with documented risk ownership and understood customer impact.

- Approve or deny risk exceptions: The CISO must run the exception process, tracking who requested it, who owns the risk, what compensating controls exist, and when it expires. This eliminates silent bypasses and open-ended “temporary” gaps.

- Set access rules teams cannot bypass: A CISO can require baseline identity controls such as MFA, privileged access controls, logging, and rapid offboarding. Crucially, they must be able to block workarounds, preventing the “just this once” access requests that later become breach paths.

- Stop unsafe vendors from entering the business: The authority to block vendors that fail minimum standards is essential. This allows the CISO to require contract fixes and limit data and system access before onboarding, protecting customers from third-party risk.

- Activate incident command with executive visibility: A CISO needs the standing to trigger incident command immediately, pulling in legal, comms, IT, and product teams. Briefing executives early with facts, options, and next steps reduces damage and confusion.

These authorities drive the current hiring demand. Organizations are realizing that a “check-the-box” security leader cannot effectively protect the business if they lack the standing to enforce difficult tradeoffs against speed or revenue targets.

The Executive Partnership Map Boards Should Expect to See

An elevated CISO operates within a web of peer relationships that define the company’s defensive posture. Boards should look for evidence of these active partnerships:

- CEO: Aligns security priorities with overall risk appetite and growth targets, ensuring the CISO isn’t fighting the business strategy.

- CFO: Collaborates on fraud loss prevention, cyber insurance adequacy, and the discipline of security spending as a percentage of revenue.

- GC (General Counsel): Partners on regulatory defensibility, customer harm reduction, and the specific language in liability contracts.

- COO: Defines operational uptime requirements and third-party delivery risks that could stall the business.

- CPO/CTO: Negotiates the “shipping velocity vs. risk controls” tradeoff in product engineering, ensuring security is built-in, not bolted-on.

If the CISO is isolated from these peers, the board must expect gaps in execution, no matter how strong the individual leader is.

The 2026 CISO Charter Boards can Hold to

In 2026, boards must look for a clear charter that links cybersecurity leadership to revenue protection, customer commitments, and operational resilience strategy.

A Short List of Business Loss Scenarios, written in Board Language

A core component of this charter is a predefined list of “loss cases” relevant to the specific business model. Rather than generic threat lists, the CISO should present scenarios like:

- Payments Fraud: An AI-driven impersonation event triggers an erroneous transfer.

- Service Outage: A ransomware attack on a critical dependency takes the core platform offline for several hours.

- Data Exposure: A misconfigured API leaks sensitive customer data, triggering regulatory fines and contract terminations.

- Insider Abuse: A privileged employee uses access to manipulate stock prices or steal IP.

Security Ownership Across the Company, not Inside a Security Silo

The charter must also clarify that security is a distributed responsibility, not solely the CISO’s burden. Boards should expect a “shared ownership” model where:

- Product Leaders own the security of the features they ship.

- IT Leaders own the patching and maintenance of the infrastructure they manage.

- HR Leaders own the background checks and offboarding processes that control insider risk.

- Procurement Leaders own the initial vetting of third-party vendors.

The CISO’s role is to set the standard, verify compliance, and report on risk, not to perform every security task personally. This distinction reduces “security theater” and creates accountable execution across the enterprise.

Resourcing that Matches Company Stage and Threat Load

Finally, the charter must align resources with reality. A mismatch here is a primary driver of CISO turnover.

- Early-Stage: Needs strong generalists and one senior leader who can “sell” security to early enterprise customers.

- Growth-Stage: Requires specialized teams for identity, detection/response, and cloud security engineering to keep pace with scale.

- Global/Regulated: Demands dedicated functions for fraud, trust & safety, and third-party risk management to handle complex compliance landscapes.

This kind of charter gives boards a practical way to assess whether cybersecurity leadership, budget and structure are aligned with the company’s risk profile.

Why Many Companies are Splitting the Job

The days of the “unicorn CISO” are effectively over. As we enter 2026, forward-thinking organizations are increasingly bifurcating the role into two distinct executive functions: a strategic CISO focused on enterprise risk and governance, and a VP of Security Engineering focused on the technical machinery of defense.

When One Leader no Longer Covers the Full Problem

This split is becoming standard in environments where the velocity of change outpaces the capacity of a single executive. This can be seen most acutely in:

- Product-led organizations that ship code daily, where security must be baked into the CI/CD pipeline rather than inspected in at the end.

- Complex cloud environments with heavy reliance on automated infrastructure-as-code, requiring deep engineering oversight that differs vastly from compliance governance.

- High M&A activity, where the integration of disparate networks creates a constant “debt load” that distracts from strategic risk management.

- AI-driven workflows that require entirely new testing and control patterns to prevent automated abuse.

In these high-pressure contexts, attempting to house both the skillsets in one person often leads to failure in both. The CISO becomes too technical for the board or too detached for the engineering team.

How to Split Responsibilities Without Gaps or Blame

To ensure this dual model functions without friction, boards and CEOs should mandate a single-page accountability view that draws a sharp line of demarcation:

- CISO: Owns the risk register, policy architecture, executive decision-making, and the “cross-company ownership map” (who owns which risk). They are the “governor” of the system.

- VP Security Engineering: Owns the delivery of security capabilities, the reliability of controls, and the tooling that enforces policy. They are the “builder” of the system.

Crucially, these two roles must operate under a shared operating plan with a single set of outcome metrics, such as “mean time to remediate critical vulnerabilities,” to ensure they are pulling in the same direction.

Reporting Structures that keep Accountability Clear

Governance structure is critical here. The emerging standard for 2026 places the CISO reporting directly to the CEO (or to the Board Risk Committee) to ensure independence from the functions they police.

Meanwhile, the VP of Security Engineering often partners tightly with the CTO or CIO, embedding security delivery directly into the technology fabric. This structure avoids the classic conflict of interest where a CISO reporting to a CIO is pressured to approve risky launches to meet IT deadlines.

Hiring demand in Early 2026

The market for security leadership is no longer monolithic. There is a distinct segmentation in the types of leaders boards are seeking, driven by specific “trigger events” that force a re-evaluation of the current security charter.

Triggers that Signal “Hire Now”

Hiring demand spikes when cyber risk starts dictating business terms. Common catalysts may include:

- Growth inflection into enterprise or regulated buyers

Security questions begin to gate revenue. The CISO role becomes part of commercial execution, not a support function. - Repeated outages or near-miss events tied to identity or vendor access

These incidents pull focus toward operational resilience strategy and decision rights around access, change control, and third-party connectivity. - M&A activity where integration risk threatens deal value

Integration speed, identity consolidation, and vendor sprawl become board-level concerns. Cybersecurity leadership needs the authority to set integration rules. - Fraud loss or abuse spikes tied to AI-enabled impersonation

This pushes AI security governance into the CFO and GC lane. The CISO role becomes a partner in financial loss reduction and customer protection. - Talent churn inside security or engineering

Attrition signals a leadership ceiling, unclear mandate, or weak operating model across enterprise leadership.

CISO Archetypes Boards are Actually Hiring

Boards and CEOs are no longer hiring a single, generic cybersecurity executive. A 2025 analysis by Forbes shows that expectations for the CISO role vary sharply based on company stage, risk exposure, and commercial pressure. In practice, executive searches tend to align around a small number of recurring leadership profiles rather than one universal mold.

Based on observed hiring patterns and role expectations described in these analyses, four archetypes consistently emerge in board-led searches:

- The Builder: Hired by late-stage startups to create the first true governance program, hire the initial team, and define the ownership map.

- The Scaler: Brought in to modernize a fragmented environment, often standardizing controls across multiple product lines or geographies to support global expansion.

- The Turnaround: A crisis-hardened leader deployed to stabilize the organization after a breach or major regulatory failure, resetting priorities and earning back executive trust.

- The Commercial Operator: A business-first CISO who focuses on removing friction from the sales process, aligning security workflows directly with revenue generation.

How to Run a Discreet CISO Search that Lands the Right Leader

Hiring a CISO at this level is a high-stakes operation. A failed search, or a “mis-hire” that leads to culture clash or breach, can set a security program back by several months.

Role Design Inputs

Success begins before the first candidate is contacted. The CEO and Board must align on three critical inputs:

- The Mandate: What specific change must this leader drive in the first 12 months? Examples include “Shift from compliance to risk-based decision making” or “Prepare for IPO readiness.”

- The Authority: Explicitly, what decisions can this person drive? If they cannot pause a launch or block a vendor, the role is advisory, not executive.

- The Stakeholder Map: Who are the key partners (CFO, GC, CTO), and is there shared agreement on what “good” looks like? Without this, the search will drift toward resume optics rather than business fit.

Interview Structure and Work Samples

The traditional interview panel is not sufficient enough for assessing strategic capability. Recommended approaches may include:

- The Work Sample: Ask finalists to prepare a 1–2 page “executive brief” on the company’s most likely loss cases and their 90-day plan to address them. This tests their ability to synthesize complex risk into board-ready language.

- Scenario-Based Panels: Instead of generic questions, run a live simulation. “A major customer demands a security feature that delays our roadmap by two months. The CRO wants to sign; the CTO wants to ship. You are in the room. What do you do?”.

Cross-Functional Vetting: Include the CFO and General Counsel in the final round to test the candidate’s ability to speak the language of finance and liability.

Retention Risks Boards Underestimate

Finally, getting the leader in the seat is only half the battle. Top CISOs leave when the “bait and switch” occurs:

- Authority Gap: If decision rights were promised but the culture allows executives to bypass security controls, credibility collapses.

- Metric Mismatch: If the role is measured solely on “zero incidents” rather than “risk reduction,” it becomes a political hot seat.

- Outcome Disconnect: If compensation is not tied to business resilience outcomes, the CISO remains an outsider to the executive team.

Conclusion

Cybersecurity leadership is entering a decisive inflection point. As we move ahead in 2026, boards are no longer treating cyber as a technical safeguard; they are treating it as a core business system that protects revenue, preserves customer trust, and stabilizes operations. This shift reframes the CISO from a functional specialist into an enterprise operator with authority that shapes product velocity, partner integration, and capital deployment.

What is emerging is not simply a “more senior” CISO, but a structurally different role: one that governs AI-driven risk, directs cross-company ownership, and negotiates tradeoffs that influence the balance between growth and resilience.

At the same time, the increasing complexity of digital environments is driving organizations to revisit their operating models: splitting the job, upgrading charters, expanding decision rights, and redefining what “good” looks like in an executive security leader. For boards, this is both a talent challenge and a strategic opportunity.

If you are reviewing cybersecurity leadership priorities and executive hiring needs, connect with Vantedge Search to discuss your leadership requirements.

FAQs

In 2026, the CISO role is expected to operate as enterprise leadership, not just a security function. The work will center on business risk decisions, operational resilience, and governance that can stand up in the boardroom.

Because cyber risk now affects revenue continuity, customer commitments, and outage cost, it is increasingly treated as a business problem. That reality pulls cybersecurity leadership into executive tradeoffs on product speed, vendors, and risk appetite.

In many companies, yes. Without clear decision rights and a direct escalation path, the role becomes responsibility without control, which slows high-stakes calls during launch or incident windows.

The reporting line should support independence and rapid escalation on enterprise risk. In many organizations, that points to reporting to the CEO or having a direct line to the board or a risk committee.

A modern CISO in 2026 needs strong executive communication, sound judgment on tradeoffs, and the ability to express cyber risk in financial and operational terms. AI security governance and fraud awareness are also becoming central to the role.

A CISO owns enterprise risk leadership, governance, and executive accountability. A VP of Security Engineering owns engineering execution, control reliability, and delivery of the security program day to day.

Leave a Reply